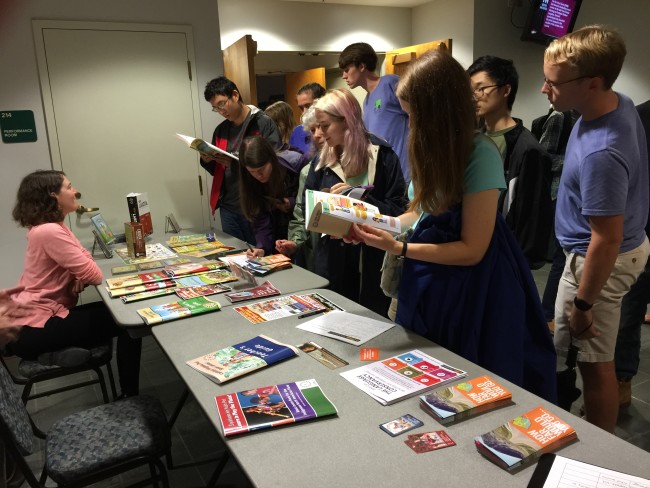

Friday Sept. 30, a crowd of linguistics students, professors and other interested parties gathered in Commonwealth Auditorium to learn about the ongoing Standing Rock protest and the attempt to revitalize the Lakota language.

The event, coordinated by the linguistics department with support from the American Indian Student Association, included a documentary, a Skype conversation with a protester at Standing Rock, a panel discussion and a question and answer session.

The panel was composed of Standing Rock resident and Lakota speaker Kevin Locke, Executive Director of the Language Conservancy Wilhelm Meya and Director of Linguistics at the College of William and Mary Jack Martin.

The documentary, “Rising Voices,” describes the efforts of the Lakota people to reinvigorate their language and culture.

Experts featured in the documentary said that by 2050, only 20 indigenous languages would exist. Currently, 6000 people, at an average age of 70 years old, speak Lakota.

According to the documentary, Lakota natives worry that their language will disappear, and with it, their culture.

The slow disappearance of the Lakota language was, in part, spurred by United States policy. In the 1800s, native children were sent to boarding schools to assimilate into United States culture, where they were punished if they spoke Lakota.

Currently, fluent Lakota speakers are attempting to prevent Lakota from dying out by attending a Summer Institute at Sitting Bull College in North Dakota, where they learn how to teach Lakota to non-speakers.

Lakota immersion schools encourage young children to learn their native language from an early age.

“In order to bring back language, you need to build unity and you need to build a team of people who trust each other,” Meya said. “We spend a lot of time building that cohesive group through our summer institutes and building a movement around language, a movement for change — a positive movement.”

Martin, who specializes in language documentation and revitalization and native languages of the American South, said that the pipeline controversy is connected to other issues, such as the extinction of languages.

“This allows us to step back and raise larger issues of the connection between the environment and other changes happening around the world,” Martin said.

Martin said that as countries choose official languages, other languages are pushed out of schools.

“Half of the world’s languages will disappear in your lifetime,” Martin said.

According to Locke, the number and diversity of indigenous languages gave rise to communication through a “silent language,” a type of sign language.

Locke taught students the Lakota words for “grandfather,” “great spirit,” and “to give thanks,” and demonstrated the corresponding movements.

The Language Conservancy looks at many different endangered languages and works with communities to create dictionaries, workbooks and cartoons to give them, as Meya put it, “the tools they need to succeed.”

Meya, prompted by a question of how a small community might reinvigorate its language, encouraged communities to learn as much as they can about their language and to maintain their passion for their culture.

“Don’t give up, even in hopeless situations,” Meya said. “Language is a powerful vehicle for change.”

Alayna Eagle Shield skyped from Standing Rock to the auditorium to answer questions about the pipeline protest. According to Eagle Shield, over 7,000 protestors have shown up to Standing Rock, which straddles North and South Dakota, in solidarity.

Eddie Santos, who works with Locke and was present at the event, said that Native American unity has sprung from the protest.

“Nobody’s ever heard of Standing Rock, but now these tribes from across the country are driving out in droves to support the unity of Native Americans and the unity of one voice,” Santos said

Eagle Shield joined the Lakota Education Action Program, enrolled her children in an immersion school and learned the Lakota language.

Eagle Shield said that her family has greatly benefitted from immersing themselves in Lakota and that she wants others in the camp to have the same opportunity.

Taking the suggestions of other residents and protesters at Standing Rock, Eagle Shield organized a place for children who were present at the camp to learn about the Lakota and their culture.

When asked about the protesters’ needs, Eagle Shield said that the residents of Standing Rock are preparing for the winter and appreciate supplies such as “tents, heaters and stakes.”

Eagle Shield encouraged non-natives to be open-minded when evaluating the Dakota Pipeline controversy. She said she wanted non-natives to consider past laws which have prevented natives from passing down their way of life to their children, and asked non-natives to reject stereotypes.

President of the American Indian Student Association Vanessa Adkins ’19 said she hopes that the audience understood that Native Americans will fight for things they believe in.

“It is empowering to know that people support you,” Adkins said.

[…] 200 people attended the Rising Voices movie screening and “Standing Rock More than a Pipeline” event we held at William & Mary College in Williamsburg, VA on Sept. 30. It included a […]

[…] Source: The Flat Hat […]

[…] 200 people attended the Rising Voices movie screening and “Standing Rock More than a Pipeline” event we held at William & Mary College in Williamsburg, VA on Sept. 30, which also included a […]