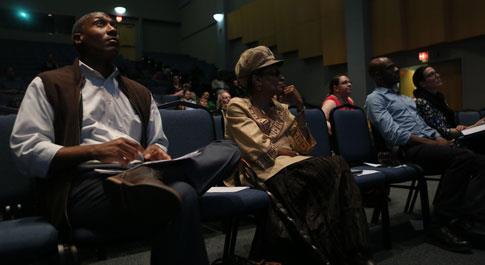

On Tuesday, Nov. 29, the Institute for Historical Biology hosted a symposium entitled “Archaeologies of Slavery and Memory in the Diaspora” in Commonwealth Auditorium. The departments of anthropology and Africana Studies co-hosted the event.

The symposium discussed the archaeological discovery of sites of slavery, reclamation and memorialization projects in descendent communities.

The symposium included presentations by the College of William and Mary’s National Endowment for the Humanities, Africana Studies Professor Michael Blakey, anthropology Professor Joseph Jones, co-director of the Remembering Slavery, Resistance & Freedom Project Autumn Barrett, and guest speaker Tania Andrade Lima.

Blakey’s presentation was centered on the African Burial Ground Project, a bio-archaeological project which analyzed the archeological history of 419 human remains of enslaved Africans buried in 17th and 18th century burial grounds in New York City.

Blakey said that the African Burial Ground Project pioneered methods of public engagement in archaeology, such as dialogue with descendent communities, which are communities affected by the re-discovery of sites associated with slavery.

“The idea of publicly engaged archaeology was developed and disseminated by the African Burial Ground Project,” Blakey said. “The term ‘descendent community,’ first offered by the project’s bio-archaeologists, has become common usage in world archaeology.”

Blakey also said that the descendent communities provide important insights that cannot be produced solely by academia. He also said that archaeologists and anthropologists must ask the permission of descendants to study their ancestor’s remains.

“It is the difference between collaboration and exploitation, democracy and slavery, love and rape,” Blakey said.

Furthermore, he said that descendants have a right to save the dignity of their cemetery and to memorialize their dead.

“It gives them the opportunity to participate in telling their own story,” Blakey said.

Blakey said that the African Burial Ground Project used historical, archaeological and biological data to explain evidence of disease and muscular strain in the human remains found at the burial ground site. He said that the transport of disease from Europe to the Americas by human carriers provides evidence of syphilis in the remains.

Methods of social control by Europeans, which involved importing more females than males from Africa in order to quell slave revolts, caused more labor to fall on female enslaved-Africans. This caused muscle strain from heavy lifting and walking.

At the end of his lecture, Blakey called for people of all ethnicities to contribute their questions and claim their stories as their own.

“Could there be a generation of young archaeologists who can follow the lead of scholars and publics who do not look like them?” Blakey said. “I’m making a particular challenge to young white people, whose histories have entitled them to a sense that they can speak for the working world, who gather data for all of humankind, somehow in an objective voice, entitled to control.”

Jones spoke about his work with the East Marshall Street Well Project in Richmond, where he is currently serving on behalf of its descendent community.

In 1994, 19th century human remains were found in an abandoned well on East Marshall Street in Richmond, Virginia. The remains were of African descent, and were believed to have been cadavers discarded by medical staff in the 1800s. The East Marshall Street Well Project, currently under the review of Virginia Commonwealth University, seeks to ensure that the remains are properly studied, memorialized and treated with dignity.

Jones, who also worked on the African Burial Ground Project, said that language is an important component to studying sites like the East Marshall Street Well Project. The African Burial Ground offered the term “enslaved Africans” in place of the word “slaves” which some have said is too dehumanizing to use in anthropological contexts.

Jones also spoke about the notion of multiple ancestries: genetic, geographic and social ancestries which tell a more complete story of the local histories of diasporic populations and are important for reconstructing historical experiences of enslaved Africans.

“These multiple ancestries are very important to take into account as we reconstruct historical experiences, and especially as we try to link those experiences to the experiences of today,” Jones said.

Jones said that social ancestry, in particular, is important because stemming from it is surrogate ancestry. Surrogate ancestry is the process of identifying surrogates who can speak as ancestors for those who cannot speak for themselves.

Jones approached the East Marshall Street Well Project using the concept of community engagement from the African Burial Ground Project. Community consultations informed the descendent community about the well project and solicited their input.

In addition, the Family Representative Council makes recommendations on behalf of descendent communities related to proper memorialization of the artifacts and remains found at the well.

Barrett was unable to attend the symposium, so Blakey read some of her presentation entitled, “Beyond the African Burial Ground.”

In the presentation, Barrett explored the feeling among African Americans that their historical narrative is distorted and incomplete and how that can lead to a sense of exclusion from the nation. She also emphasized that community engagement is an integral part of the memorialization of enslaved Africans.

Lima, Chief Archaeologist on the discovery of the Valongo Wharf in Rio de Janeiro, presented the symposium with an international perspective on the re-discovery of sites associated with slavery.

Valongo Wharf was a port in downtown Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where an estimated 500,000 enslaved Africans disembarked. The excavation was prompted by the decision to remodel parts of Rio de Janeiro for the Olympic games. The government intended to replace old slave landscape with modern structures.

However, Lima said that archaeologists have the historical responsibility to shed light on Brazil’s past which she sees as being shameful. In this way, archaeology plays an activist role.

“Archaeological knowledge should be placed in the service of social causes and thereby contribute to the development of emancipatory policies for oppressed groups ultimately for greater social justice,” Lima said.

Lima said that it is necessary to recognize that the stigma of slavery still exists among Brazil’s poor black populations who live in undignified living conditions. She said that civic engagement and dialogue can raise awareness and inspire tolerance and respect.

Lima said that she hopes that someday Valongo Wharf can be a place of liberation and celebration, but that it is up to the community to decide what to do with its own heritage.