Once a home to slaves, Colonial Williamsburg seeks to commemorate and honor the city’s rich history of African-Americans through a variety of programs and events during Black History Month each February.

This year, visitors will be able to engage directly with a spectrum of historical artifacts, live interpretations, acclaimed films, museums and special events around Williamsburg. Stephen Seals, responsible for community outreach for Colonial Williamsburg, recounted the experience of a particular sensation — sound — that affected him emotionally when he went to the First Baptist Church to ring its Freedom Bell, an opportunity that will be available for all visitors during the month of February.

“I was surprised at how emotional it made me to ring that bell and think about the history of the bell, what it’s been through, what I’ve been through,” Seals said. “I rang it for friendship, and I rang it there with a really good friend. We rang it and we both started crying and hugging. It’s very emotional when you ring it and you feel the history of that church….”

The Freedom Bell, despite dating back to 1886, stood mute for over 50 years due to mechanical issues. However, the bell was restored in February 2016. After its restoration, thousands of people of all different backgrounds, both from the United States and as far as the United Arab Emirates, visited First Baptist Church to ring the Freedom Bell. Online, a virtual Freedom Bell created for those who could not come to Williamsburg, was rung by seven million, according to Brown. It is a sound that even former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama heard in September 2016 when the bell traveled to Washington, D.C. to be rung at the opening of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

“I feel like telling these stories, as well as connecting the bell, as well as talking about everyone who lived within the buildings helps to connect all of us,” Seals said. “Because as divisive as America is right now, the only way we’re ever going to get better is together.”

The opportunity for guests to ring the Freedom Bell is only one activity of many to take place during Black History Month in Colonial Williamsburg. Seals has helped in the coordination of live performances set in the Kimball Theatre, including one called “Journey to Redemption.” In this show, the actors break the fourth wall and talk to the audience about the challenges of acting the difficult parts of both enslaved peoples and slavers. Seals could empathize with these challenges given that he, in the past, acted the part of a slave. Seals underscored the difficulty of playing the role of a slave as a black man, but he also pointed out the parallel challenges of white actors playing slave masters who must convincingly personify characters with beliefs so contrary to their own.

Among other live shows, there will be a “REV Talk” presented by culinary historian and writer Michael Twitty, who has traveled extensively and studied the intersection between food, culture and history as it relates to African and African-American people.

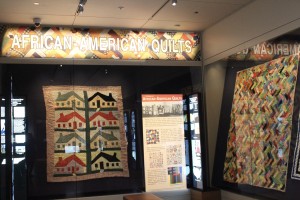

At the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, the exhibit “A Century of African-American Quilts” weaves in the narratives of African-American quilters with its showcase of a rich patchwork of art made mostly during the 20th century. Surrounded by a host of shapes and colors ranging from powder blue polygons, red-checkered rectangles and satiny squares of lavender, black and beige, the exhibit envelopes viewers in the history of African-American quilters. Christina Westenberger, Assistant Manager of Education at the museum, discussed the different ways one can view a quilt — not just as a piece of art, but as something to put on a child’s bed to keep them warm, or to use as a picnic blanket, as batting for the making of a new quilt or as something to bury someone with. Westenberger cited how one quilter, Susanne Allen Hunter, would burn pieces of her quilts, creating smoke to get rid of the bugs in her small, two-room house in Georgia, as her windows did not have screens or glass.

Westenberger discussed how these quilts can shed light on the lives of particular quilters and can open up an even wider lens of historical background. She spoke of how an exhibited quilt made by Helen McWhorter Simpson led her to learn about the history of “Free Frank,” or Frank McWhorter, an enslaved man from South Carolina who bought his freedom and traveled to Illinois, where he founded the town New Philadelphia, making him the first African-American man to found a town.

“That’s an amazing story — I never would have known that story if it hadn’t been for this object,” Westenberger said.

Kimball Theatre will be featuring several movies throughout its “Films of Faith and Freedom” series, an event that first took place in February 2016. While last year’s series focused on the history of slavery and abolition, this year, Director of Entertainment Robert Currie and Program Manager Marianne Johnston decided to explore the canon of films created by black filmmakers and producers.

“We wanted to sort of show the creativity, strength and power of not people who just make films about African-Americans or black history, but people who have … had personal experience and touches with that from childhood,” Currie said.

The theatre will be showing several films that present both historical and contemporary interpretations of the African-American experience. For example, “Loving,” a story about an interracial couple battling the Supreme Court for their right to live together as a family, is set in Virginia during the 1960s. In a more contemporary time, the 2017 Golden-Globe Winner for “Best Motion Picture — Drama,” “Moonlight,” follows the story of a young, black man growing up in Miami.

“We wanted to sort of show the creativity, strength and power of not people who just make films about African-Americans or black history, but people who have … had personal experience and touches with that from childhood,” Currie said.

Seals, Brown, Johnston, Westenberger and Currie noted that their programming dealing with African-American heritage will not be confined to just the month of February, but is set to span the entire year. Currie said that at least one film per month will stem from the same theme of faith and freedom central to Black History Month in Colonial Williamsburg, beginning with a screening of the Oscar-nominated film “Hidden Figures” in March.

Overall, Seals said African-American programming has been going on since 1979, but the framing of the narrative has evolved over the years. He expressed hope that guests would be able to absorb a more comprehensive picture of African-American history and slavery.

“What I want more than anything else is for guests to see that the enslaved person might have been enslaved under the letter of the law, but they didn’t see themselves as slaves,” Seals said. “They saw themselves as mothers, and as fathers, and as carpenters, and as lovers, and as haters, and good people, and bad people, that they saw themselves in humanity, that they saw themselves as people, and I think what you’re seeing more and more of is that we’re telling more rounded stories.”

Brown and Ethell Hill, another representative of First Baptist Church, stressed that it is important for today’s youth to learn about the experiences of past generations. Brown and Hill both recalled witnessing tumultuous violence decades ago in their pasts — images of overturned cars burning, rifles, dogs and hoses remain in their memories today.

Despite darkness in America’s history, Brown emphasized an optimistic outlook for future generations.

“We want kids to understand that the future does not have to be bleak for them just because these things have happened,” Brown said. “It really is up to them to determine what kind of future they want to have. We’re hoping it’ll be a more positive one, better than what we have experienced. It can always be better, there’s always room for improvement.”

Seals corroborates the value of storytelling and engaging in the events taking place this February and beyond in Colonial Williamsburg, especially in terms of understanding ideas of American identity.

“The story of the African in America is not a black story, but it’s an American story,” Seals said. “I think this programming … helps people — hopefully that don’t look like me, and those that do look like me — to understand that the history of America, no matter whose history it is — the slave people, free, rich, poor, politician.”

According to Seals, connecting to this past identity will help us move forward as a nation.

“I feel like telling these stories, as well as connecting the bell, as well as talking about everyone who lived within the buildings helps to connect all of us,” Seals said. “Because as divisive as America is right now, the only way we’re ever going to get better is together.”

[…] Read the full article from the Source… […]

[…] Read the full article from the Source… […]

[…] Read the full article from the Source… […]