American Naturalism is quite straightforward.

As John Spike, Assistant Director for the College of William and Mary’s Muscarelle Museum of Art, explained, “Naturalism just means, ultimately, life-like.”

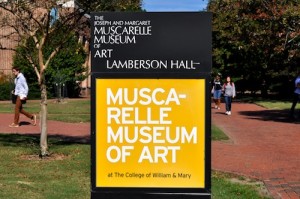

The Muscarelle’s “American Naturalism” exhibit, which includes impressionistic works, has been on display since Feb. 8 and will remain on display until Jan. 11. The collection of 10 paintings, rendered in the 19th or early 20th century and lent to the museum by the Owens Foundation, is the first thing one sees upon entering the exhibit. Most of the paintings depict nature, a subject matter that, unlike many others, can be admired by everybody. And yet, the paradox of the exhibit — and to a degree, a larger Muscarelle problem — is that it seems like no one has seen it.

“No one” may be an overstatement, used predominantly to describe the lack of student attendance. Since “American Naturalism” was unveiled, 8,046 people have visited the museum. Only 734 of those visitors were students. It’s unclear whether the students were visiting the Muscarelle for the exhibit or just casually visiting the museum as a whole. If “American Naturalism’s” opening week is any indication, it was likely the latter: 26 students visited during opening week, which is only slightly higher than the mean of approximately 21.5 student visitors per week during that time period.

“Frankly, I’m kind of amazed that since everyone’s walking by here — it’s an excellent location — that they don’t just stroll in here and take a peek,” said Spike.

On the afternoon of Friday, Oct. 3, Kim Bond ’15 was doing just that.

“I just came for the Muscarelle,” said Bond. “It’s really calming in here. There’s not many people, and you can really forget about everything else outside.”

But Bond wasn’t particularly impressed by naturalism.

“Naturalism is okay. I’m more into post-impressionism — more, I don’t know, the surprise colors. Like, you wouldn’t expect a bridge to be pink, you know.”

Bond’s apathy toward the collection provided an interesting juxtaposition to Spike’s enthusiasm.

“People like impressionism more than any other style,” Spike said. “They like impressionism because it’s a sunny day. And if it isn’t a sunny day, well, the rain looks rather nice for some reason. Right?”

The painting that Spike was referring to, Edward Potthast’s “Bathers in the Surf,” depicts a group of women enjoying the ocean on a sunny day at the beach. It’s the image the Muscarelle used to promote the exhibit.

Spike recommended “Bathers in the Surf” as a good painting to start with.

“We can see [Potthast’s] hand in these brush strokes, and yet it has a nice vivacity and a sense of spraying us in the face,” he said.

One of the other highlights of the collection is Robert Henri’s “Portrait of Mrs. Haseltine.” It stands out as a rather large portrait, strategically displayed in the middle of the teal colored wall, surrounded by a collection that consists mostly of landscapes.

“So people will settle on one thing and not just see them in a row, you tend to put the most important picture in the center of the wall,” Spike said. “At any rate, what [Robert Henri and a group of painters he belonged to, called ‘The Eight’] wanted to do is move away from the glamour of Victorian society and show people more warts and all. And the way this is done — you see in this very broad way; if you look at it close up it’s not so realistic.”

The exhibit certainly has highlights, but as Muscarelle benefactor Patty Owens said, “Any one of those artists, for the most part, someone who is involved in the art world would definitely know them. Many of them are represented in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.”

On the other hand, “Celebrating the American Scene,” the exhibit that neighbors and complements “American Naturalism,” according to Spike, does not have a particular highlight, and was produced by less accomplished artists. Yet, students are drawn to the exhibit because of its approachability.

“In a strange way, amateur or beginning painters feel a sort of sympathy towards the artists who are less impressive technically,” he said. “They see it a little bit closer to where they are today.”

Given the pervasive subject matter — the natural world — of American Naturalism, it’s a bit ironic to hear the exhibit described as one that’s not the most approachable for students. But it makes sense: The featured artists are renowned in the art world, but virtually anonymous outside of it — they’re American, but not quite contemporary, and the paintings are gorgeous, but not flashy, not sexy.

When asked what she thought of Theodore Earl Butler’s “Les Regates,” one of the more vivacious pieces in the exhibit, Bond replied, “It’s just like all cool colors, which doesn’t interest me as much. It’s not as dynamic, you know. There isn’t a play with the hot. And there isn’t a lot of drama to the painting.”