A refugee panel sponsored by the No Lost Generation student group and featuring three government professors was held Wednesday, Feb. 15. The panel was created in response to the refugee crisis and President Trump’s recent executive orders concerning immigration.

Rani Mullen described the refugee crisis broadly in global terms, Rebekah Sterling delved into President Trump’s executive orders and their implications and Debra Shushan spoke about how the crisis occurred and its effects.

Mullen emphasized that refugees are not a new phenomenon, as there have been refugees throughout history, but she said the crisis is especially dire right now. She said that it is also important to keep in perspective that refugees are not the only displaced people; the number of internally displaced people is nearly twice as high.

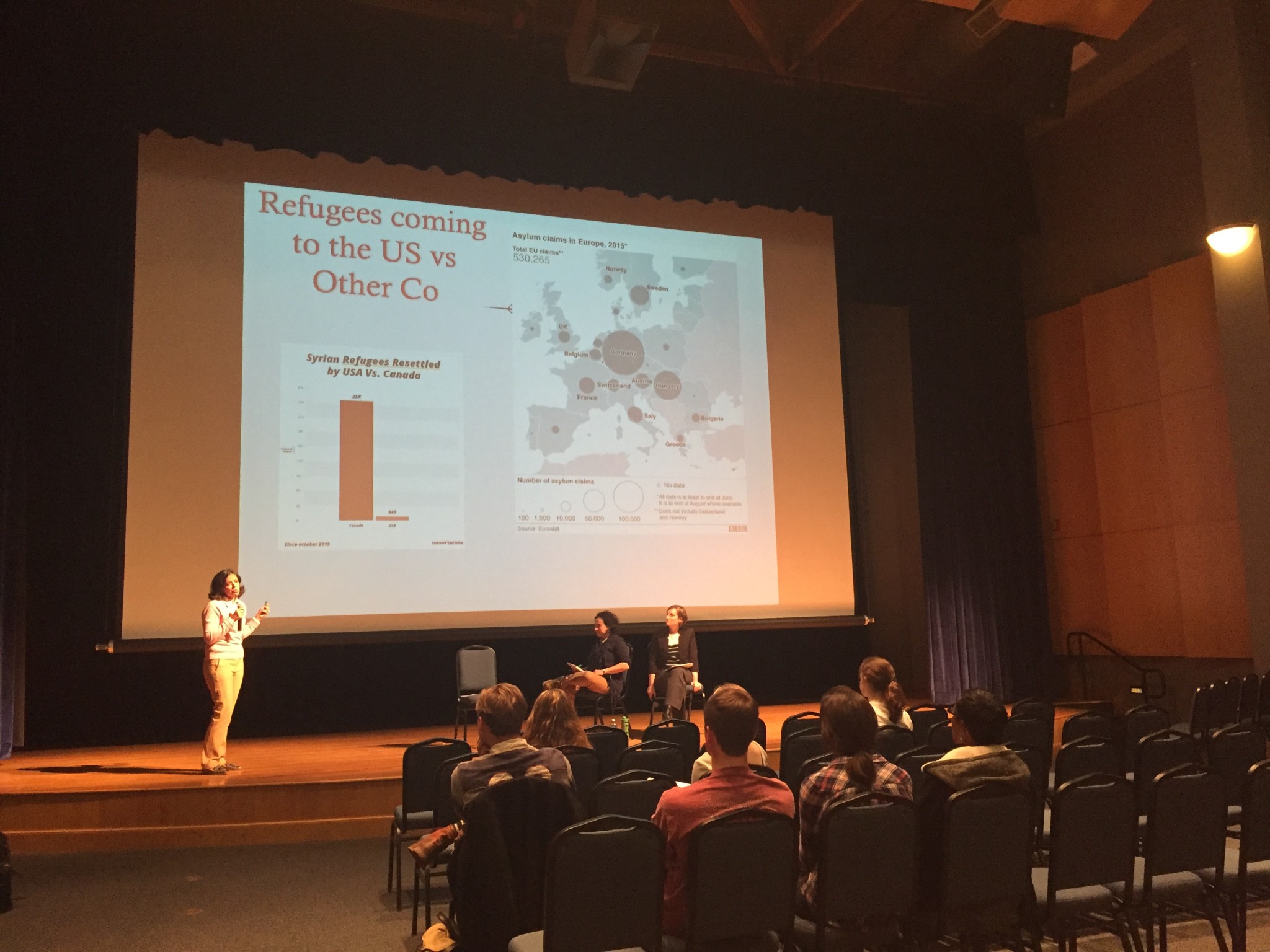

Of the global population displaced by conflict in 2014, 19.5 million are refugees, 38.2 million were internally displaced and 1.8 million had asylum claims pending. She also emphasized that developing countries were taking more than their fair share of refugees and certainly more than developed countries, at about 86 percent.

Of the refugees from Syria, the country from which the majority of refugees are fleeing, 95 percent are hosted in just five countries: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt. 95 percent of Afghan refugees are hosted in just two countries: Pakistan and Iran.

We, living in rich countries are taking a small fraction of refugees,” Mullen said.

“We, living in rich countries are taking a small fraction of refugees,” Mullen said.

Mullen said refugees are coming mainly from Syria and Afghanistan, but also Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Myanmar, Central African Republic, Iraq and Crimea. She said reasons for displacement include medical needs, women and girls at risk, children at risk, survivors of violence and torture, and family reunification. She said in most cases people are fleeing violent conflict in their home countries and only recognized refugees whose life, liberty, safety, health or other fundamental rights are at risk in the host country are considered for resettlement.

In addition, refugees cannot pick their country of resettlement. She said The UN Refugee Agency flags vulnerable cases for possible resettlement and refugees themselves cannot apply for resettlement. Less than one percent of the world’s refugees are ever resettled.

“We are talking about very small numbers [being resettled],” Mullen said. “Especially when we talk about it in terms of what is fair, who has a global responsibility to help out.”

Sterling explained the recent executive orders. She said the one that has gotten the most attention suspended travel and the other two focus on immigration enforcement. Sterling said this will lower the amount of refugees the United States takes in overall. She said the language and content of these executive orders suggests that Trump’s policy surrounding asylum seekers is linked to immigration. She said it further explicitly links immigration to safety and security.

“[It’s saying that] aliens who enter the U.S. illegally will present a threat to national security and public safety,” Sterling said.

Sterling said that there are different ways for refugees to seek asylum in the United States. At the beginning of every fiscal year, the president and Congress decide how many refugees they are going to take in. In the current fiscal year that number was raised to 110,000.

The executive order from Jan. 27 proposes cutting that number to a maximum of 50,000. A refugee can gain asylum in the United States and become one out of this number if they go through the up to two-year-long screening process that is conducted abroad and are accepted at the end of it. After that, they are assigned to one of nine NGO’s (six of which are faith-based) by the Department of State. That NGO then helps them to find work and settle in. However, Sterling said that over the past few years, there has been a shift in deterrence policy for asylum seekers. There are stricter requirements and an increased number of asylum seekers in detention centers. In 2014 the United States had 44,000 asylum seekers in detention centers.

“These changes fit in what scholars call and increasing securitization in immigration policy,” Sterling said.

Shushan then explained the Syrian refugee crisis, because Syria is the generator of the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers. Shushan said 400,000 Syrians have died in the war there which is now approaching its seventh year. Shushan said 4.9 million Syrians have fled the country and there are 6.6 million internally displaced persons.

Shushan said that Turkey and Lebanon have taken the largest number of Syrian refugees, together housing four million Syrian refugees. She said that last year in August, the United States filled the pledge to bring in 10,000 refugees. She also said that the acceptance of such large numbers of refugees by Turkey and Lebanon has severely damaged those countries’ economies.

Shushan concluded with a personal anecdote, relaying the story of her mother’s Jewish family living in Poland during World War II but her mother being able to find refuge in the United States.

These policies have tremendous consequences,” Shushan said. “I would not be here today if my family as refugees were not able to come to the U.S.”

“These policies have tremendous consequences,” Shushan said. “I would not be here today if my family as refugees were not able to come to the U.S.”

A public commenter from the wider Williamsburg community, Hyasinter Rugoro, shared her experience as a refugee with the panel and the audience. She relayed her experience of growing up in the jungle in a refugee camp when her parents were exiled in Rwanda and said she learned to read and write through song. Rugoro told the story of how she made it to the United States with her fiance but once he finished school, they were told they had to leave. She said they could not go back to Rwanda so within a week, they packed up and sought asylum in Canada, where they are now citizens. She emphasized the importance of recognizing that refugees are humans, not statistics and have stories like hers.

“These stories have a human face,” Rugoro said. “They are sitting among us. Thank you and encourage you to keep doing what you’re doing.”