The music of the 1970s was defined by many things, including electronic instrumental progressive rock, wild on-stage performances and speech synthesis.

For many people, the synthetic sounds that riddle Pink Floyd albums, KISS’s fire-blowing guitars and the first videogame sound effects symbolize this decade. By extension, these people are thinking about the work of John Elder Robison.

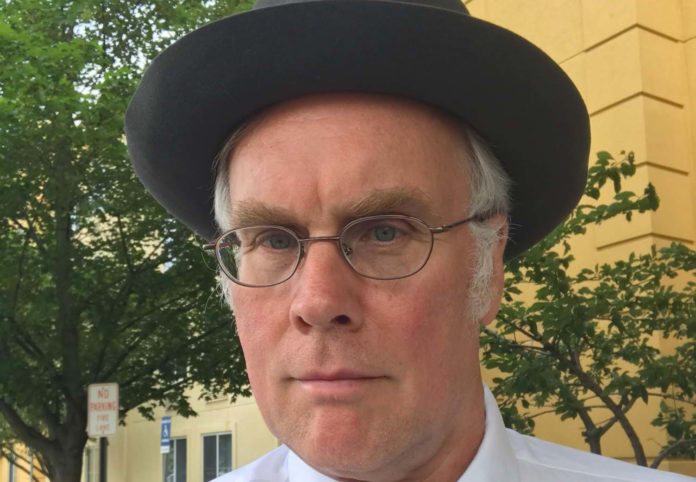

Robison is the faculty advisory for the student neurodiversity group as well as the co-chair of the neurodiversity committee at the College of William and Mary. As a man living with Asperger’s syndrome, he uses his personal experiences to lead the neurodiversity movement on campus and serve as the College’s Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence.

Asperger’s syndrome falls on the higher-functioning end of the autism spectrum and is a form of neurobiological difference. One of the defining characteristics of Asperger’s is a lack of social skills.

“I didn’t have a good sense of the difference between other kids and me,” Robison said. “I believed that I was right and you were wrong, and I was showing you something, and you rejected it. And I had no idea what I did wrong. … I had no concept of other people having separate thoughts and I had absolutely no idea why they didn’t want to be my friend … I just assumed there was something wrong with me.”

Robison experienced trouble in school and recalled disagreements he had with the fundamentals that were taught and the stringent grading, specifically in math and in English. In English classes, he did not appreciate the emphasis on grammar at the expense of content. In math classes, he did not understand why he’d only receive credit for a correct answer if he wrote out all his work for a problem.

When school did not prove to be his strong suit, Robison took to electronics.

“I had a gift for figuring out how musical signals were processed by electronic devices,” Robison said. “It wasn’t actually that I was born with that, it was that I spent thousands of hours taking things apart and putting them together. First I destroyed things, radios and TVs, and then I could fix them, and then I could build them.”

His competence with electronics and his innovative ideas are what opened the door to the world of music for Robison. He worked as an engineer for both Pink Floyd and KISS in the late ’70s to early ’80s.

When KISS asked if he could make a guitar blow fire, Robison did not hesitate.

“I had been told I was such a loser and to see that, it was really cool,” Robison said. “I think that’s probably the high point of touring for me.”

Despite his success in the music and electronic industries, Robison quit because he feared he was not good enough. He opened his own car repair business and built up a reputation for himself by getting to know his customers.

One day, one of his regulars who was a therapist came in with a book about Asperger’s syndrome. He suggested that Robinson may have the condition.

“All my life I had had the ‘diagnosis of the street,’ you know, that you’re a reject, you’re stupid, you’re lazy, you’re retarded, you’re mental, all these things people would say,” Robison said. “After a lifetime of that, hearing a nonjudgmental neurological explanation, it was really liberating.”

“All my life I had had the ‘diagnosis of the street,’ you know, that you’re a reject, you’re stupid, you’re lazy, you’re retarded, you’re mental, all these things people would say,” Robison said. “After a lifetime of that, hearing a nonjudgmental neurological explanation, it was really liberating.”

After reading the book, Robison realized that there were behavioral tricks he could use to improve his social interactions. It was these learned mannerisms that led to him writing and speaking about neurodiversity. Robinson wanted to help young people who, like him, could not conceive that people might simply see the world as “fundamentally different” from themselves.

“You know, if you’re not autistic, you might think: well how simplistic and how obvious,” Robison said. “You don’t even think about a thing like that. But if you’re a person who’s failed at social interaction all your life, that’s like getting the keys to the castle … it’s transformative.”

In addition to his mission to advocate for neurodiversity, Robison was drawn to Williamsburg for its ancestral ties. Rowland Jones, Robison’s ninth grandfather, was the first minister to preach at Bruton Parish Church. His eighth grandfather, Orlando Jones, was an early student and an usher of the grammar school at the College, as well as the Williamsburg representative in the House of Burgesses.

Robison speculates that his ancestors were also autistic. This lead him to wonder if there is a point in time at which the world’s views shifted from valuing the differences presented in people on the autism spectrum to making them feel like less-intelligent outsiders. This question drove him to the field of education.

Now, Robison co-teaches three courses in neurodiversity with history professor Karin Wulf, his co-chair of the neurodiversity committee. The College offers a four-credit COLL100 course in the spring, a one-credit elective in the fall and a one-credit continuing education course at the College of William and Mary Washington Center during the summer.

To Robison, one cannot decide what to do for a population of people without the participation of said people. This belief is another reason he started writing and speaking on behalf of the neurologically diverse community.

“We’re different, and the world needs different,” Robison said. “Because there will be times when the other 90 percent of the world tries to solve a problem and they can’t do it. And because we think differently, we see the answer just like that.”

“We’re different, and the world needs different,” Robison said. “Because there will be times when the other 90 percent of the world tries to solve a problem and they can’t do it. And because we think differently, we see the answer just like that. And maybe most of the rest of the time we’re disabled and we say funny things and we don’t know what to do, but if we can solve that problem one time out of 10 when nobody else can, the world needs us.”

The William and Mary Neurodiversity Student Group, led by co-presidents Chloe How ’20 and Alanna Van Valkenburgh ’20, meets Wednesdays at 7 p.m. in the third-floor lobby of Blow Memorial Hall.

The group believes in the neurodiversity paradigm, which advocates that neurological differences increase human diversity and should be both accepted and appreciated. It serves as a non-judgmental place of learning for both people interested in neurodiversity and students who are neuro-divergent themselves.

“I think that so often, people who are autistic learned about autism because they were failing at something, and so they associate autism with failure,” Robison said. “… One thing we want to show with the neurodiversity group is that people who are different can be stars, and it’s more than just failure. That’s one of the things we’re about, showing people what we can be.”

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!