The discovery of the picture of two men, one in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan hood and robe, on Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s medical school yearbook page prompted a mass reexamination of the pasts of the state’s political leaders. The picture was swiftly and widely condemned as racist by Democratic and Republican political leaders.

The College of William and Mary has not been excluded from this reckoning. College President Katherine Rowe released a statement to the campus community a few days after the revelation announcing that Northam would not appear at last Friday’s Charter Day ceremonies as scheduled.

Virginia Senate Majority Leader Thomas K. Norment J.D. ’73, the highest-paid adjunct professor at the College, also faced criticism when reports revealed he was managing editor of a 1968 Virginia Military Institute yearbook replete with blackface pictures and captions, which included racial slurs. The College declined to comment on this incident in Norment’s past.

In response to the recent discovery of racist images in other Virginia university yearbooks, similar to the one in Northam’s edition from the Virginia Military Institute, the College is taking steps to confront its own history by currently conducting an audit of all of its yearbooks.

“Earlier this week, President Rowe asked University Archives to perform an audit of all yearbooks for both imagery and content that is counter to our values of diversity and inclusion,” Whitson said.

“We are aware of past yearbooks with racist images,” College spokesperson Brian Whitson said in a written statement. “Earlier this week, President Rowe asked University Archives to perform an audit of all yearbooks for both imagery and content that is counter to our values of diversity and inclusion. That is underway. This review will help inform that deeper understanding of William & Mary’s racial history as we work together as a community to ensure this is the kind of respectful and welcoming campus we want and expect.”

Past indiscretions

Less than a century ago, minstrel shows with white minstrels singing and dancing in blackface would not have raised an eyebrow at the College. Colonial Echo yearbooks include College minstrel troupes well into the 1930s. The 1925 Colonial Echo even boasts of the successful creation of a Girls’ Minstrel Troupe, which included a “rag doll dance” and a “colored quartette.” In 1958, the Chi Omega sorority page in the Colonial Echo shows 12 white sorority sisters, four of whom are dressed in full minstrel blackface.

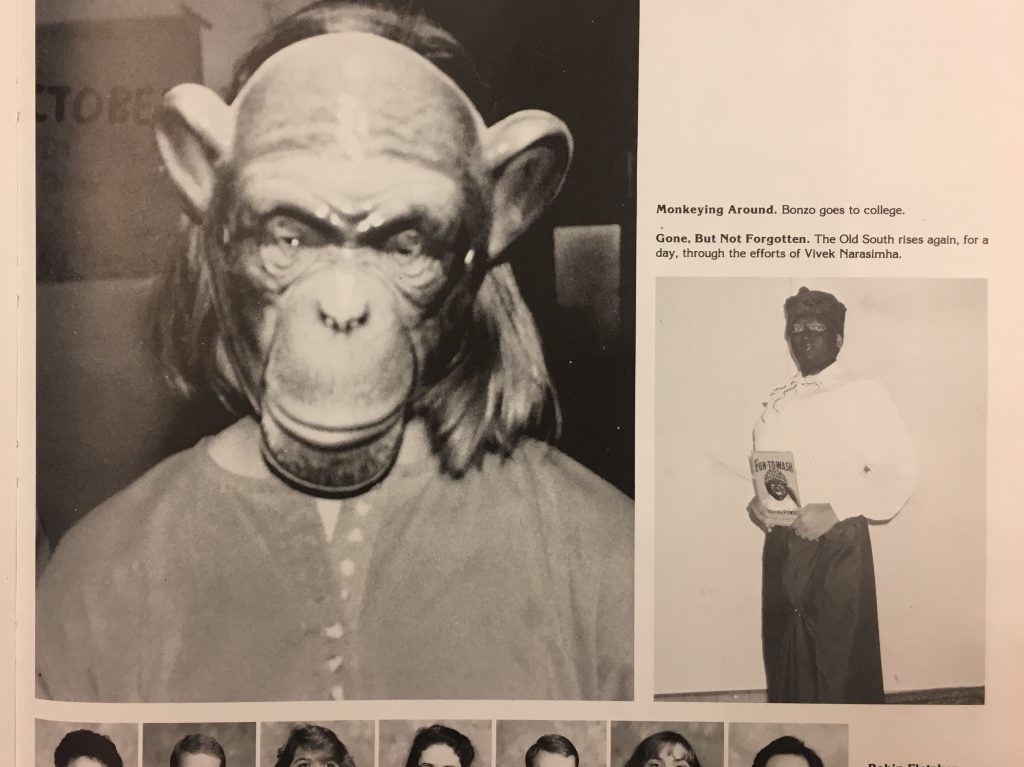

Even after the College admitted its first African-American students in residence in 1967, racist pictures continued to appear in yearbooks. When the 1991 Colonial Echo included a picture of a student in minstrel blackface holding a logo for a baking powder company depicting a “mammy” figure and captioned “Gone, But Not Forgotten. The Old South rises again, for a day, through the efforts of Vivek Narasimha,” it provoked a flurry of responses among the student body.

Several editorials were published in The Flat Hat that year in response to the publication of the blackface picture. A letter to the editor published Nov. 15, 1991 co-authored by four students — Jane Carpenter ’92, Karla Carter ’93, Jenee Gadsden ’93 and Tiffany Gilbert ’93 — condemned Narasimha and the staff of the Colonial Echo.

“Thank you, Colonial Echo,” Carpenter, Carter, Gadsden and Gilbert said in the letter. “Thank you for reminding blacks that a time in our history — that represents pain, struggle, degradation, and suffering — has not been forgotten by you. Seeing that picture in the Colonial Echo gave us an even more acute sensitivity to the racial climate that pervades this campus. Racism exists everywhere. Sadly, this incident has driven home the point that ignorance and racist stereotypes continue to be tightly woven within the mental fabric of many students at William and Mary.”

In January 2015, a “Golfers and Gangsters” themed mixer between Kappa Alpha Theta sorority and Sigma Pi fraternity faced backlash due to costumes that played into negative stereotypes of African Americans. Witnesses described seeing white students dressing up as “bloods” — the primarily African-American Los Angeles street gang — by wearing costumes made up of tight tank tops, sagging sweatpants, basketball shorts, bandanas and drawn-on face tattoos of teardrops and gold chain necklaces. The same week, Kappa Delta Rho fraternity faced criticism for hosting a “War of Northern Aggression” themed party which resulted in the fraternity being placed on social probation.

The College has become increasingly cognizant of its legacy of racism and has taken steps to address its past. This has most notably occurred through the establishment of the Lemon Project in 2009, which studies the College’s role in perpetuating slavery and racial discrimination, as well as the Task Force on Race and Race Relations, which was led by Chief Diversity Office Chon Glover M.Ed. ’99, Ed.D. ’06 and released a comprehensive report regarding its findings in 2016.

“We know that William & Mary has its own troubling history with regards to race and racism,” Whitson said in an email. “Through the Lemon Project and the Task Force on Race and Race Relations, we have made progress over the past decade in understanding and reckoning with our past but there is more work to do.”

Origins of blackface

According to theater and Africana studies professor Artisia Green ’00, blackface minstrelsy, which originated as a distinct performance style in the United States in the 19th century, is inextricably tied to a glorification of institutionalized slavery in the United States.

“Blackface minstrelsy in America began as a comic device used by whites to create nostalgia around institutionalized slavery and to shape attitudes about black images and culture,” Green said in an email. “… Blackface minstrelsy as a coerced performance had roots in plantation slavery, where the enslaved were commanded to perform artistically and sexually for the entertainment and pleasure of whites and/or to demonstrate, via the auction block, their marketability.”

Green went on to say that while there is a general consensus that blackface and Klan insignia are symbols of prejudice and intimidation, she believes many people are not aware of how much harm these symbols can cause.

“What continues to surprise me is that there remains an unwillingness to accept the fact that embracing these symbols outside of thoughtfully curated educational contexts will cause harm,” Green said in an email. “Given that we have access to so much scholarship on these two phenomena, I believe that to blacken-up or impersonate a Klan member is a political choice and an overt display of bigotry, prejudice, and racism. One’s whiteness does not make them a blank slate absent of historical and social markings or a canvas upon which blackness — and faulty interpretations at that — can be drawn upon.”

History professor Melvin Ely studies African-American and Southern history. He has written extensively about “Amos and Andy,” a radio show where two white actors played black characters. According to Ely, blackface would not have been uncommon during the turn of the 20th century at a place like the College.

“The use of blackface and those tropes were commonplace in American culture generally, not only Southern culture, from the 1840s and through much of the 20th century,” Ely said. “So without having investigated it myself, I would suspect that if you went back through William and Mary artifacts, you’re going to find that sort of thing. What is well documented here is the fact that William and Mary was a college attended largely by slaveholders, the sons of slaveholders, that it as an institution held enslaved people as property.”

Ely said that the reason blackface is offensive to so many people is that it is not merely a costume but an extreme and mocking caricature of an oppressed group of people. While blackface minstrelsy became less popular over time, it continued to be practiced well into the 20th century. Though Ely has largely dedicated his academic career to studying blackface, he admitted he still found himself taken aback by the discovery of the picture in Northam’s yearbook page.

“But believe me, there are more out there,” Ely said. “And if I were them, I’d be thinking, ‘OK, when does the shoe drop for me?’”

“In the Northam case, whether or not that’s him in the picture, the picture is pretty shocking,” Ely said. “The blackface would already be appalling and shocking and it surprises me in 1984. But the juxtaposition of that with a Klansman just exponentially makes it worse.”

While the Northam image proved jarring to Ely, he said he would not be surprised to discover many more racial improprieties in Virginia politicians’ pasts.

“Just as when the #MeToo [movement] started, there are plenty of guys who have done this stuff, and a number have been outed by now,” Ely said. “But believe me, there are more out there. And if I were them, I’d be thinking, ‘OK, when does the shoe drop for me?’”

The politics of power

While blackface stands out as one of the most visible examples of racist behavior, other College traditions from the past have contributed to a glorification of antebellum, slave-holding Virginia.

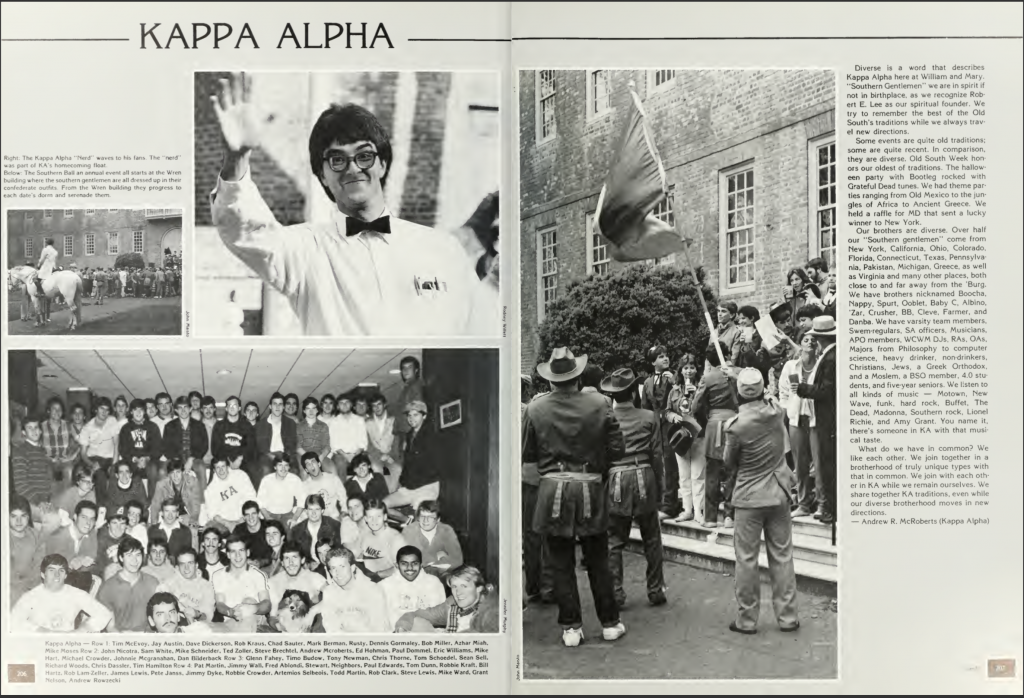

In the 1920s, the College offered a slew of eugenics courses, which employed pseudoscientific arguments to argue white racial superiority. The College band performed the civil war anthem “Dixie” at football games until 1969. Through the end of the 1970s, the College’s chapter of the Kappa Alpha fraternity organized an annual “Southern Ball and Weekend” where fraternity members dressed in Confederate uniforms would parade down Duke of Gloucester street, present a sword to a College administrator and symbolically secede from the College for a weekend in Virginia Beach.

History professor Jerry Watkins researches Southern history; this fall, he taught a freshman seminar on Dixie monuments which addressed many of these issues in the classroom. Watkins explained that in many ways the College set the tone for racial conversations in the era of minstrelsy. Lyon Gardiner Tyler — the namesake of the history department — wrote anti-black books such as “Confederate Catechism,” which emerges as an example of the era’s pervasive racist attitudes.

To Watkins, the crux of the issue is not that no one knew that blackface was wrong. People of color knew that blackface was wrong, and people who worked to advance social justice issues knew blackface, and other demeaning traditions, were wrong. Yet, Watkins contended, the privileged white student body and administration of the College did not listen to those voices for a long time.

“There were a lot of people who saw minstrelsy, who saw blackface, who saw Kappa Alpha,” Watkins said. “There are lots of people who saw that as a problem — but the ones with the power and the ones with the privilege didn’t.”

“There were a lot of people who saw minstrelsy, who saw blackface, who saw Kappa Alpha,” Watkins said. “There are lots of people who saw that as a problem — but the ones with the power and the ones with the privilege didn’t.”

In 1971, the Black Student Organization at the College wrote letters to the editor in The Flat Hat criticizing elements of the Kappa Alpha parade as “obnoxious, offensive and threatening to black people.” The BSO organized counter marches, but the Kappa Alpha march took place annually until at least 1977. Only in 2010 did the executive council of the Kappa Alpha explicitly forbid its members from wearing Confederate uniforms during fraternity events. Watkins argued that what has changed now is not the inherent moral perception of blackface as a racist practice, but a shift in who is able to command dominant narratives.

“People have been saying for 100 years that blackface is a problem,” Watkins said. “But now we are in a moment where enough people with enough cultural capital and enough power are saying, ‘Yes, that is also a problem,’ and are agreeing with it.”

The hard work of reconciliation

History professor and Lemon Project Director Jody Allen Ph.D ’09 specializes in African-American history, including Reconstruction and the Jim Crow Era. According to Allen, blackface minstrelsy used to be the norm, and acted as a method of whites trying to control the black population in the South by projecting stereotypes that mocked them by their clothes, accents and attitudes.

“A lot of this is about maintaining power, and until we become comfortable with giving up some of that power, there are people out there who will do anything and say anything and perpetuate anything to maintain it,” Allen said. “We have to be aware of that and acknowledge it where it is, that these symbols, these ways of being, the blackface, all of that I think boils down to keeping black people in their place. And again, keeping them where you think their place is helps you maintain your power.”

Allen argued that even as the prevalence of blackface minstrelsy has lessened, many attitudes toward and stereotypes of black people have remained present in American culture in different ways.

“I think in this country, we’re still fighting some of these stereotypical notions of who and what black people are,” Allen said. “And a lot of that comes from this time period [of minstrelsy].”

Allen said that when it comes to politicians like Northam, Herring and Norment, who were raised in educational environments where racist depictions of African Americans were alive and well, it is difficult not to consider how those biases might impact their policies today.

“If you are a thinking person, you can’t help but wonder: What does he believe now?” Allen said. “And how does this impact my life?”

“I think that there are definitely those moments and those opportunities for all of us to learn and grow and become who we are to be, but at the same time sometimes those attitudes don’t change,” Allen said. “So I think that has to be part of the conversation. What if he still has those beliefs but now he’s just been caught? So that’s part of the kind of conversation I think that has to happen. … If you are a thinking person, you can’t help but wonder: What does he believe now? And how does this impact my life?”

While part of the Lemon Project’s mission is to study the College’s past, another is to promote reconciliation efforts. Allen said that she believes the College has been doing this up to now. To Allen, the letter sent by College President Katherine Rowe to the campus community last Monday explaining the Charter Day speaker change and condemning blackface was an example of the College’s commitment to upholding that mission.

“I think that letter struck the right chord of support for the community,” Allen said.

Rowe’s letter was notable to Allen because it represented an acknowledgment by the administration of how painful Northam’s yearbook image was to black students at the College.

“If he had been allowed to come here [on Charter Day], there would have been people who would decide not to go, would have decided not to participate,” Allen said. “Some would have gone and would have protested it. It would have been clearly communicated that the school really doesn’t care about me.”

While the College is currently taking steps to reconcile with its past similar to many other Virginia institutions in the wake of similar revelations, Allen stressed that awareness of these issues cannot be limited to condemning blackface.

“The work continues,” Allen said. “But I think William and Mary is committed is committed to doing that, and getting the story out … and I think that bodes well for the school.”