“Tree to Mountain,” an exhibit showcasing over two dozen woodblock prints by Japanese artist Toshi Yoshida, opened at the College of William and Mary’s Muscarelle Museum of Art Oct. 17. The exhibit’s journey from Japan to the College is an unlikely one: associate professor of history Hiroshi Kitamura grew up living next door to the Yoshida family in Kamakura, a small city just north of Tokyo.

Two summers ago, Yoshida’s son Takashi told Kitamura that one of his father’s woodblock prints, “Baobabu and Rhino,” had been acquired by the Muscarelle. Kitamura suggested that the Muscarelle host an exhibit of Yoshida’s work, and use “Baobabu and Rhino” as the feature image. Both Takashi and the Muscarelle were very supportive of the idea.

“What I wanted to do was introduce Japanese and East Asian cultures to William and Mary, which has a long tradition of European influence,” Kitamura said. “And while I think the Yoshida family is known in art circles, they deserve more opportunities to be showcased.”

The obscurity of the Yoshida name presented a potential obstacle to the Muscarelle, which has had trouble attracting students to exhibits of more well-known artists’ work in the past.

To elicit interest, the museum hosted “Kabuki to Sushi: An evening of Japanese Culture at the Muscarelle Museum of Art” Nov. 7. On a typical day, the Muscarelle might attract five or six students. But “Kabuki to Sushi” was quite a happening.

“We ended up getting 562 students to come, and 491 of them actually went into the museum — which is a great ratio. It’s better than we had for, I think, Caravaggio last year,” said Internal Affairs Coordinator and Special Events and Advancement Fellow Laura Wood ’16.

The greater turnout for an exhibit of works by a lesser known artist can probably be attributed to the free sushi at the event. The $5 wine likely didn’t hurt either.

But while most of the students in attendance were drawn to kabuki by sushi —rather than the opposite order insinuated by the event’s title —it seemed like most of the 491 students who made their way into the museum were pleasantly surprised by the art itself.

“I thought the art itself was impressive, and unique and different from what I was used to seeing,” Adam Siegel ’15 said. “That was the first time I had been inside the Muscarelle, and I thought it was pretty cool.”

The exhibit was curated by Kitamura, art history professor Xin Wu and a small group of students enrolled in a one-credit course on Japanese woodblock curation taught by Kitamura and Wu.

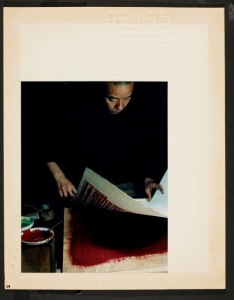

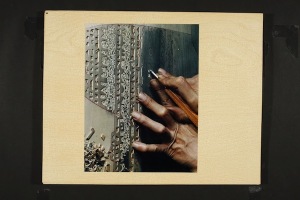

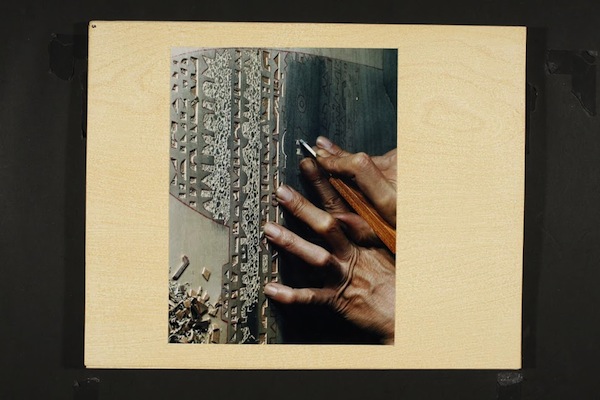

“Students and I — we actually got together in the spring, met to conceptualize the exhibition and choose the prints,” Kitamura said. “We wanted to show how technical this art is. Because you have the original sketch, and you have to carve that in to create a master image, and then the more colors you add, the more carvings you need. So if you have 20 colors, each print has to go through like 10 or 20 print processes. So this is a tremendously labor-intensive, elaborate technique.”

The difficulty and technicality of woodblock printmaking is conveyed to patrons through a video explaining the process, and through a series of sketches at the center of the exhibit, highlighting the different steps of the process. However, the video and the sketches are contradicted by the finished pieces hung on the walls. Yoshida’s work spans nearly 50 years, and makes printmaking look easy.

The prints are animetic — director Hayao Miyazaki’s animators study them, according to Kitamura — and adventurous with a sense of movement. Yoshida was a world traveler and his prints depict areas as close as San Francisco, as far as the East African plains, and as forbidden as Havana.

Notably, the first two prints in the series, “Hirosaki Castle” and “The Chion-in Temple Gate,” were not made by Yoshida; they were made by his father, Hiroshi Yoshida, who played an integral part in reviving traditional Japanese woodblock printing.

“He was a real staunch, controlling patriarch, and he was really trying to have Yoshida produce prints that fit his design,” Kitamura said. “Toshi had really ambivalent feelings about his father. On the one hand, he learned everything — the nuts and bolts of printmaking — from his father; but he also rebelled against him.”

The arrangement of the prints — grouped semi-chronologically, by subject matter — makes the progression of Yoshida’s rebellion easy to see. His father’s prints are followed by his own Japanese scene prints, animal prints and then foreign scene prints.

“What I really liked was the attention he paid to the work his father had done. But he also, you know, broke away from it, especially in terms of subjects,” Aidan Selmer ’17 said. “I think he liked to acknowledge that his dad lived mostly in Japan, but he also went overseas to Africa. And he really tried to apply the techniques of his father and put them in a new setting.”

In a town that can feel stuck in the past and in a museum with a predilection to the West, “Tree to Mountain” is an escape from time and from place.

“My favorite compliment I got that night,” Wood said of the Kabuki to Sushi event, was that “someone said ‘This is great. I don’t even feel like I’m in Williamsburg.’”

[…] A Touch of the East at the Muscarelle […]