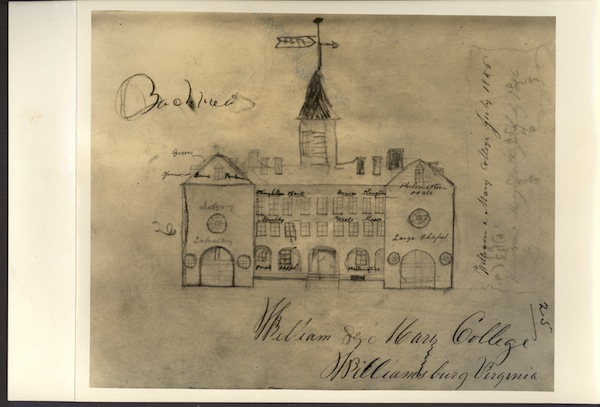

Today is the College of William and Mary’s 321st birthday. Take some time to remember why we celebrate the charter that now allows us to attend this esteemed university. In order to appreciate what we now have, we must remember our origins, if only just to see how much this campus has physically improved since its beginnings.

What began as a three-building campus now encompasses over 15 academic buildings, the Sunken Garden, a football field, an indoor arena and over 50 dormitories and on-campus houses.

In the 17th century, Queen Mary was interested in the endeavors of the colonists to build the university, so when Reverend James Blair visited the King and Queen in England, they granted him a charter for the school Feb. 8, 1693, with Blair — the progenitor of the project — as its first president.

They bought a parcel of land 330 acres from Captain Thomas Ballard — who had previously bought it from Thomas Ludwell. On that site, they built what we now call ancient campus.

In 1694, there was a ceremony for the laying of the foundation of the College’s first building, but work went slowly and the Sir Christopher Wren Building was completed between 1695 and 1700.

After the Wren Building burned down — for the first time — in 1705, it wasn’t until 1709 that the Trustees were able to acquire the funds to rebuild it. Royal Gov. Alexander Spotswood was a major contributor of this endeavor.

By 1712, Spotswood had convinced — or coerced — many young Native Americans to enroll in classes. Funded by Robert Boyle, the Indian school was built in 1723. Today, it is known as the Brafferton and holds administrative offices. When it first opened, the Brafferton was usually used as a dormitory. Students who didn’t receive housing had to secure residence in a local tavern or house.

Two of three proposed additions to the Wren Building had been added by 1732, including the chapel wing. That same year, the foundations were laid for the President’s House. In 1786, the French government paid reparations for damages done to campus by its army during the war.

Fire struck again in the Wren Building in 1859 and 1862. In the fall of 1865, after the American Civil War ended, the College reopened the building. In 1868, classes were suspended in order to fully rebuild and repair, and in 1869 classes resumed when the Wren Building’s repairs were complete.

The colonial area of campus was, for many years, the entirety of campus. While campus continued to expand, this section remained the focal point for the design and placement of campus buildings.

“You all call it Confusion Corner now, but when I was really little, you couldn’t walk past College Corner without seeing a group of men sitting on the brick wall,” Executive Director of Historic Campus Louise Kale said. “Back then we called it Jockey Corner, and you know why? Because in the ’50s and ’60s, students used to have to retrieve their mail at the Williamsburg post office downtown, so the girls would powder their noses and the boys would sit on the brick wall like jockeys and watch the girls go pick up their mail.”

In 1908, the College began to expand behind the Wren Building when the cornerstone for the new library was laid. The library was moved from the space behind the Wren chapel and renamed Tucker Hall. Tyler Hall, originally a men’s dormitory, opened in 1916 and was refurbished to be an academic building in later years.

With the enrollment of women in 1918, there was a need for new dorms. Jefferson Hall — originally a women’s dormitory — was built along Jamestown Road and opened in 1921. The basement of Jefferson used to have a gymnasium as well as pool for use by female students. Three years later, men’s dormitory Monroe Hall was completed along Richmond Road.

“Campus during the years after the inclusion of women was completely divided between sexes. The Richmond Road side was men’s with all the men’s dorms, the stadium and the Blow Hall gymnasium and pool. Women’s facilities were located along the Jamestown Road side with their own athletic field and own dorms,” Kale said. “Men were allowed to call in the parlors of the women’s dorms during certain hours, but they were not ever allowed upstairs, and dorm mothers made sure of that.”

In 1926 Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall was built next to the Wren Building; the old Phi Beta Kappa Hall caught on fire and was renamed Ewell Hall when it was rebuilt.

A year later, Washington Hall opened as a general classroom building. During this same time period, from 1928 to 1931, John D. Rockefeller was helping to fund and oversee the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, as well as the Wren Building, the President’s House and the Brafferton.

1935 saw the construction of the Sunken Garden, which opened the area between both sides of old campus. Before the Sunken Garden was built, the area was just a dense field of grass.

A great many additions and changes to the College campus came during the 1950s, the most important of which was the attendance of the first African American graduate students in 1951. Undergraduate African American students were not admitted until a decade later in 1963.

In 1953, Bryan Hall, Dawson Hall, Stith Hall, Camm Hall and Madison Hall opened and formed what is now the Bryan Complex. Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall as we know it now was built in 1957 to create a new space for student performances.

1960 marked the opening of the Campus Center — to accommodate housing offices, student publications, theater, ballrooms and new dining areas — as well as Yates Hall. The Adair Gymnasium opened in 1963 while DuPont Hall and Small Hall both opened in 1964.

The Earl Gregg Swem Library finally opened in 1966. It was intended to be the focal point of new campus. However, the move required the help of many students who helped employees transfer books from Tucker Hall to the new library in boxes.

Our historical campus has been expanded, destroyed, dedicated and re-dedicated — and it can be hard to keep up with the shifting names and locations. Despite the hardships and the fires that have scorched through the most integral parts of campus, the College still stands and is more expansive than ever before.

Read more about the groundbreaking, weird and occasionally disastrous history of the College of William and Mary.