Racism is commonly associated with concepts of violence committed against minorities, disparate educational opportunities and unfair treatment by the police. During a lecture March 30 as part of the Black Lives Matter Conference at the College of William and Mary, students discussed another form: environmental racism.

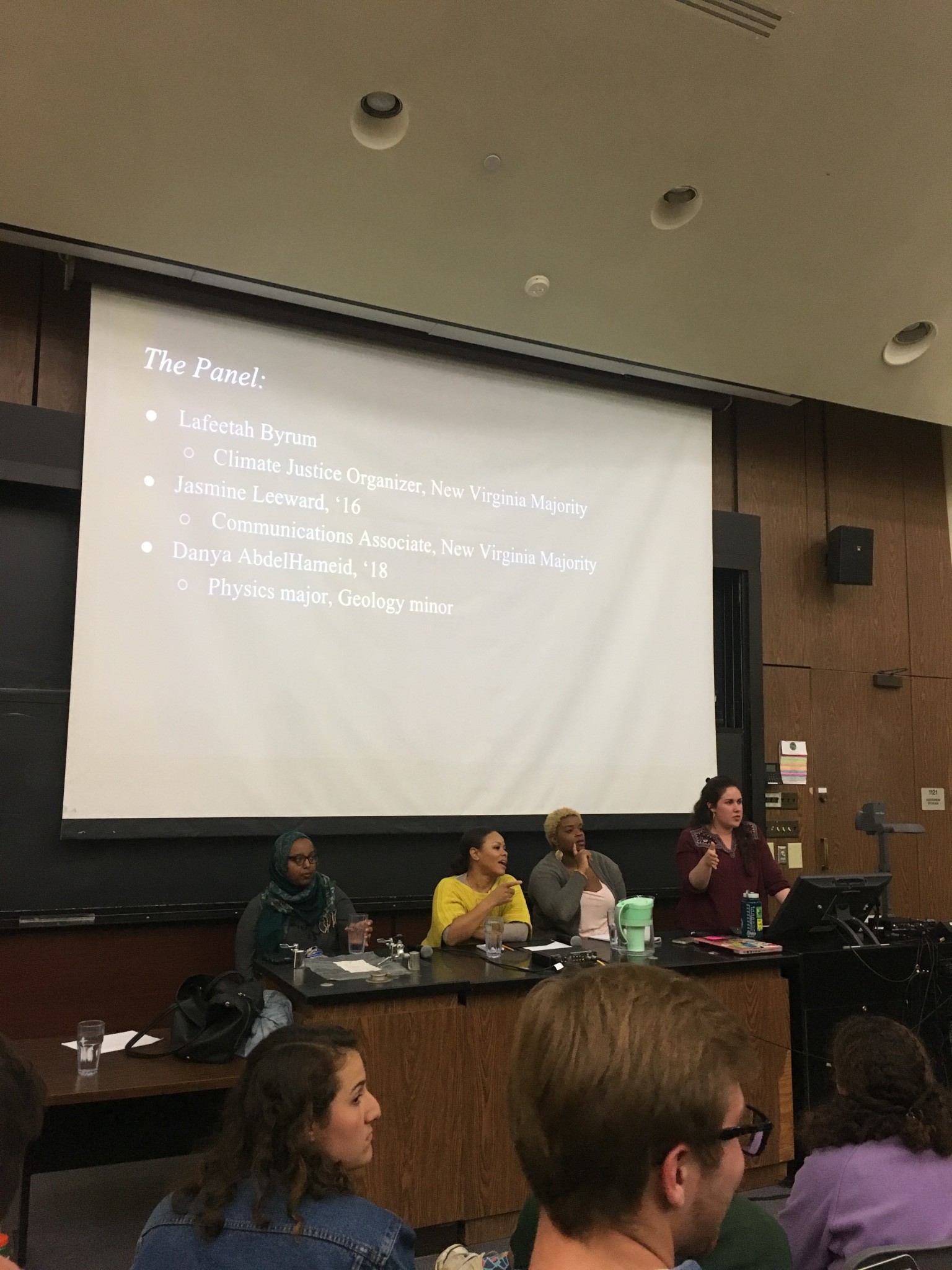

Over 100 students gathered in a lecture hall in the Integrated Science Center for a panel discussion on environmental racism. Panelists were New Virginia Majority Climate Justice Organizer Lafeetah Byrum, New Virginia Majority Communications Associate Jasmine Leeward ’16 and Danya Abdel-Hameid ’18. Megan Embrey ’17, a representative from the Student Environmental Action Coalition, moderated the event. Other students, including Hayes Parker-Kepchar ’18, Ben Milburn-Town ’20, Maura Finn ’20, Madeline Salino ’20, Brendan Thomas ’18 and Natalie Steinberg ’17 also helped coordinate the event.

The panelists said that their goal for the lecture was to demonstrate that environmental injustice and racism are linked and highlight environmental racism’s intersectionality. Additionally, they said that they wanted to expand the mainstream narrative of environmentalism that is often limited to “wearing Birkenstocks and making your own granola.”

The panelists defined environmental racism as the phenomenon by which “socially marginalized communities are subjected to disproportionate exposure to pollutants and denied access to sources of ecological benefits, such as clean air and water.”

Byrum used the example of Norfolk Southern, a Hampton Roads-based transportation company, improperly covering coal, which she said causes public health concerns, like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchitis, that disproportionately affect black people because of geographic location.

Leeward shared another example of environmental racism — U.S. President Donald Trump’s plan to withdraw the Clean Power Plan, initiated under former U.S. President Barack Obama.

By rolling back the Clean Power Plan, already one in six black children have asthma as a result of the environment that a lot of them live in,” Leeward said. “Under the umbrella of systematic racism, I think is environmental racism. It’s one of the ways that racism plays out in your life. Within 1.8 miles of toxic waste dumps or an industry that causes a lot of pollutants, 50 percent of the population that lives in that 1.8-mile radius is African-American.”

“By rolling back the Clean Power Plan, already one in six black children have asthma as a result of the environment that a lot of them live in,” Leeward said. “Under the umbrella of systematic racism, I think is environmental racism. It’s one of the ways that racism plays out in your life. Within 1.8 miles of toxic waste dumps or an industry that causes a lot of pollutants, 50 percent of the population that lives in that 1.8-mile radius is African-American.”

According to Byrum, New Virginia Majority’s work hinges upon the participation of the community.

“The overall goal of our work is to have the community be engaged in the legislative process, because that’s the real way that we’re going to affect change on this issue, is to legislate tougher laws against where trash is dumped … and placing regulations on industries,” Byrum said.

Abdel-Hameid said that her family’s background and her personal experiences have opened her eyes to the importance of environmental justice.

“The experience that really got me interested in environmental justice was actually when I was 11 or 12,” Abdel-Hameid said. “As I mentioned, my parents immigrated to the U.S., and my family has roots in Sudan, and that was the first time that I had gone back to Sudan. A lot of my family that lives there, lives in a way that is very different from how I live here.”

When asked how white people who may not directly experience the harms of environmental injustice can support the issue, members of the panel agreed unanimously about one thing.

“I don’t think that it can happen without diversity [in environmental organizations],” Leeward said, followed by nods and snaps of agreement.

Byrum said that the best thing for white environmentalists to do is to support the work led by African-American environmentalists at the grassroots level.

“It’s really important to redefine the way that people look at environmental activism and their place in being an activist for environmental justice,” BLM organizer Damiana Dendy ’17 said.

Dendy said that many people consider themselves environmentalists but don’t necessarily focus on communities of color, and that should be changed.

A theme of this conference is to be aware of the history that’s come before, to be aware of the activism that has come before you,” Dendy said. “You have to know what has happened in the past in order to move forward effectively.”

“A theme of this conference is to be aware of the history that’s come before, to be aware of the activism that has come before you,” Dendy said. “You have to know what has happened in the past in order to move forward effectively.”

According to Dendy, this issue is particularly important right now because of the state of U.S. politics.

“This fits into BLM because as I said, this issue is rooted in racism against communities of color,” Dendy said. “This week is all about redefining how you see the Black Lives Matter movement as well as activism in general.”