*NOTE: This is the final installment in a series on former government professor David Dessler. It explores how Dessler’s story relates to the culture surrounding mental health at the College and provides closing thoughts on the case’s significance.

By Meilan Solly

In April 2015, the College of William and Mary garnered national attention after experiencing four student deaths, including two confirmed suicides, in one academic year. The Washington Post described the death of Paul Soutter ’17 as a “tipping point” for a community that had witnessed eight student deaths since 2010. Alumna Cassie Smith-Christmas ’06, whose brother Ian Smith-Christmas ’11 committed suicide in April 2010, penned an open letter questioning the College’s approach to mental health.

On campus, the atmosphere was just as somber. Students organized mental health initiatives, including an April 29, 2015, walk held in honor of Soutter, Peter Godshall ’15 and Saipriya Rangavajhula ’17. College administrators hosted an open conversation on suicide prevention.

Former government professor David Dessler, then-president of the Faculty Assembly, said he observed these events with increasing frustration. During the summer of 2015, he consulted with local medical professionals regarding the College’s mental health climate, and by the start of the 2015-16 school year, he had drafted plans for a student-faculty mental health initiative.

Sept. 11, 2015, Dessler announced the initiative to students in his sections of Introduction to International Politics and Theories of the International System. He disclosed his personal struggles with mental illness, including a bout of depression that led him to take medical leave in spring 2007, but added that he was not ashamed of seeking treatment for these issues.

The classes’ responses, according to both Dessler and former students, were deeply impassioned.

“I [asked], ‘Why are you so emotional about this?” Dessler said, “and one student said, ‘You’re breaking down walls.’”

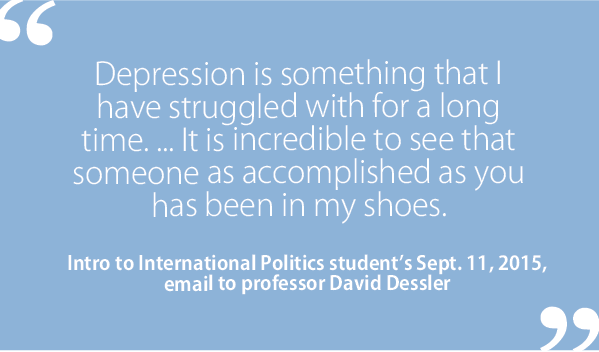

Later that day, several students sent Dessler messages of support.

“Depression is something that I have struggled with for a long time,” one wrote in an email. “…It is incredible to see that someone as accomplished as you has been in my shoes.”

Throughout the fall 2015 semester, Dessler continued promoting frank discussions of mental health. He made plans for the initiative’s first event — a panel featuring professors speaking about personal experiences with mental illness, as well as medical professionals offering advice on suicide prevention — and incorporated psychology principles into his courses.

Nick Flanagan ‘18, a student in Introduction to International Politics, explained that Dessler occasionally launched into seemingly off-topic stories but always connected his anecdotes back to mental health or related social science concepts.

“They would always end very poignantly,” Flanagan said. “I don’t know anyone [else] who can tell a story where I don’t know what’s going [on] and then I feel like I learned something.”

At the beginning of October, Dessler’s sister passed away. Over the following weeks, he canceled multiple class sessions, citing grief and the additional stress of his ongoing divorce settlement.

Oct. 21, Dessler sent students an email that would have lasting repercussions. In it, he wrote that he had been hospitalized but would return to campus in time for class.

“I am very sick, and I believe I do not look good, because everyone agrees on that,” Dessler said. “But we finally got the right diagnosis yesterday; things will be fine in the long term; and things are highly unpredictable and unpleasant in the short term. Don’t be alarmed.”

According to Dessler, the Oct. 21 email was a teaching exercise designed to mimic the perspective of an individual suffering from psychosis. He planned to use the message in his introduction of implicit assumptions’ role in starting World War I, but due to fatigue and grief, failed to disclose these intentions.

According to Dessler, the Oct. 21 email was a teaching exercise designed to mimic the perspective of an individual suffering from psychosis. He planned to use the message in his introduction of implicit assumptions’ role in starting World War I, but due to fatigue and grief, failed to disclose these intentions.

Dessler never made it to the day’s classes. Instead, the William and Mary Police Department barred him from entering the classroom. Professor John McGlennon, then-chair of the government department, dismissed students, who did not have a chance to speak with Dessler. Less than a week later, McGlennon informed students that Dessler was on administrative leave and would be replaced by a new instructor.

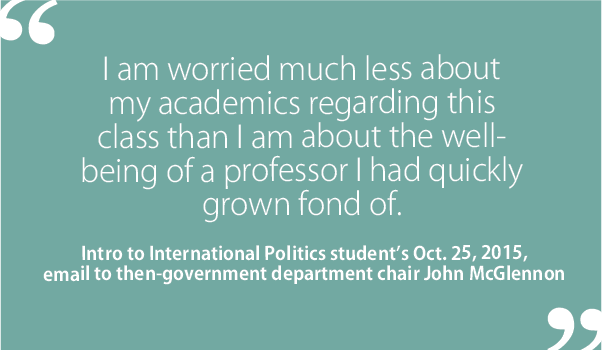

Students and parents offered mixed reactions to the unusual situation. Some expressed confusion and sadness over Dessler’s departure, while others voiced safety concerns sparked by their former professor’s cryptic emails.

“I am worried much less about my academics regarding this class than I am about the well-being of a professor I had quickly grown fond of,” one student wrote in an Oct. 25 email to McGlennon. “…I am disappointed in the lack of transparency we as students have been presented with and I feel that all of the drama surrounding this incident only serves to perpetuate the stigma surrounding mental health at this school.”

Oct. 27, a parent contacted McGlennon with “major concerns regarding the safety of his former students.”

“I’m sure that Professor Dessler was advised to discontinue all communications with his former students, yet he continues to write rambling letters,” the parent wrote in an email. “With that said, how does the school plan to guarantee the safety of their students and staff? … Unfortunately, far too many times people who express or show signs of mental illness and have the propensity to harm themselves are ignored until a tragic incident occurs.”

The Flat Hat has covered the ensuing series of events — from Dessler’s decision to take leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act to his multiple arrests for alleged harassment by computer and a recently filed discrimination lawsuit against the College — but not within the context of the administration’s approach to mental illness.

A Nov. 5, 2015, FMLA certification form states that Dessler went on leave due to “grief, difficulty with focus and maintaining routine.” Dessler further explained that this period of leave, as well as the erratic emails he continually sent to colleagues and students, were related to a condition called acute psychiatric trauma.

In late 2015, Dessler experienced a steady flow of traumatic events. He said the distress caused by these events was comparable to that of a damaging yet treatable physical “blow,” as opposed to a persistent illness.

In July 2016, Dessler was also diagnosed with a disorder on the bipolar I spectrum — his doctor classified it as “eminently treatable,” and his current diagnosis is bipolar I in remission.

“I’ve had trauma and been successfully treated,” Dessler said. “I’m much better now. There were a couple of periods, October 2015 [and] just last June, when I was really struggling, and you can see it in the emails I wrote. [But] you can work through those traumas and they will not have a long-lasting effect.”

Between Feb. 28, 2016, and Jan. 13, 2017, Dessler spent a total of 77 days in jail, including 45 on charges that were later dropped. During these periods, he had no access to prescribed medications and few opportunities to seek medical care. Although his time in jail was jarring, Dessler said that living in constant fear of arrest ultimately had a stronger negative impact on his mental health.

Former Provost P. Geoffrey Feiss, one of three emeritus faculty members who wrote a Sept. 8, 2016, letter of support for Dessler to the Faculty Assembly and Provost Michael Halleran, said he had serious concerns about the administration’s handling of the situation.

Former Provost P. Geoffrey Feiss, one of three emeritus faculty members who wrote a Sept. 8, 2016, letter of support for Dessler to the Faculty Assembly and Provost Michael Halleran, said he had serious concerns about the administration’s handling of the situation.

“If someone is mentally ill, you don’t put them in jail,” Feiss said. “We haven’t done that since the 18th century. We don’t do that anymore, [and] the fact that this was a resolution of their sense that he was mentally ill was devastating.”

Chancellor Professor of English Emeritus Terry Meyers, one of the memo’s co-authors, said he decided to write the letter in response to a perceived violation of the Faculty Handbook and Dessler’s due process rights.

He also added, however, that the College’s “rapid deployment of campus police” following Dessler’s Oct. 21 email seemed like an abuse of power.

“In some sense, the College seems have criminalized what appears to be erratic behavior by someone afflicted with an illness,” Meyers said. “I would have thought compassion would be called for in this instance and I am mystified as to why David was treated as he was.”

An additional concern raised by both Feiss and Dessler was the latter’s extended isolation from the College community. In addition to being banned from campus, Dessler was prohibited from contacting students, McGlennon and College employees other than Chief Human Resources Officer John Poma.

“The only people he could communicate with were people … who were retired and therefore outside [of] the purview of the institution, and that is a terrible thing to do to someone who the institution believed to be suffering from mental illness,” Feiss said.

Dessler compared his isolation to that of Ian Smith-Christmas, the student whose April 2010 suicide spurred his sister to write an open letter questioning the College’s mental health policies.

According to the letter, Cassie Smith-Christmas advised her brother to visit the Counseling Center after learning he was having suicidal thoughts.

“Instead of offering any help, they call my mom to come down and then at 5 p.m. that day, [March 18], hold a meeting with a dean and five other staff where they promptly dismiss my brother from William and Mary and ban him from College grounds,” Cassie Smith-Christmas wrote.

Ian Smith-Christmas sought treatment at a local mental health facility and was released on outpatient status roughly two weeks later. Although doctors recommended he return to school that same week, the College denied his initial application for re-admittance. April 24, soon after he was finally allowed to return to campus, Smith-Christmas committed suicide.

“I do not hold William and Mary responsible,” his sister wrote, “[but] the way they treated him certainly contributed to how lost he must have been feeling to make such an awful decision.”

Dessler said he found the College’s decision to ban Smith-Christmas from campus reflective of a “tradition specific to William and Mary” — one in which individuals with serious mental health issues find themselves isolated from the community. He added that this treatment strategy contradicts the dominant advice offered by mental health professionals, who suggest sticking to one’s normal routine and staying connected with friends and community.

“I think one of the main problems with William and Mary is there is a culture that promotes silence,” Dessler said. “…Students know the system is broken and many of them don’t take advantage of the mental health resources for that reason.”

Following the publication of Smith-Christmas’ letter, Vice President for Student Affairs Ginger Ambler ’88 Ph.D. ’06 responded to recurring concerns about the College’s approach to mental health, including those later cited by Dessler.

She wrote that almost 40 percent of students who visit the Counseling Center report suicidal thoughts, but the majority remain enrolled at the College. Those whose situations are best suited to taking time off from school are still considered students in good standing, and the College is “committed to supporting [them] in transitioning successfully back to our community.”

More than two years have passed since Dessler last stepped on campus, but he said he remains committed to the issue of student mental health, both at the College and on a wider scale. Just this month, he launched Syntiro, a non-profit organization dedicated to teaching faculty how to support students with mental health issues. The overall goal, he explained, is to promote an environment in which individuals can discuss mental illness without fear of stigmatization.

“I have such a complex set of reactions [to what happened], a lot of sadness but also … hope for the future, and I would say that I’m also concerned because I’m no longer a professor,” Dessler said. “I can’t do anything about what’s happening in terms of student mental health at the College. It’s been a difficult experience but not without its rewards. I … leave concerned about students who have this fundamentally broken system. If that conversation could just get normalized on campus, everything would be great.”

By Sarah Smith

Two years after former government professor David Dessler was first placed on administrative leave, he began developing Syntiro, a nonprofit organization that aims to address the state of mental health on college campuses.

In an interview with The Flat Hat, Dessler identified the state of student mental health at the College of William and Mary as a “tipping point” in his own struggles with mental illness. In September 2015, he proposed a joint student-faculty mental health initiative to promote open conversations on campus. According to legal documents, he now believes that the proposed initiative made him a target of discrimination within the government department and eventually led to his June 2017 resignation.

Following Dessler’s announcement of the joint mental health initiative and the start of his medical leave later that year, he said he had limited opportunities to engage with other faculty members. He also said that he did not know what other faculty members thought of him. In emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, The Flat Hat found that many government professors, including Kay Floyd and Sue Peterson, who assumed responsibility for teaching Dessler’s classes after his departure, did not know the full story.

Following Dessler’s announcement of the joint mental health initiative and the start of his medical leave later that year, he said he had limited opportunities to engage with other faculty members. He also said that he did not know what other faculty members thought of him. In emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, The Flat Hat found that many government professors, including Kay Floyd and Sue Peterson, who assumed responsibility for teaching Dessler’s classes after his departure, did not know the full story.

Dessler said that over the course of his three decades at the College, the government department was supportive of him and recognized his academic work. He confided in several colleagues, including another professor with a diagnosed medical condition, and received support from then-department chair John McGlennon when he took medical leave for his depression in 2007. Dessler said, however, that faculty members in general do not openly discuss mental health issues.

“I think professors have just as much trouble talking about it as anybody else,” he said. “It doesn’t matter what your age or level of professional experience or training or something [is]. … People are scared to talk about mental illness because the reactions can be so negative, just from your friends, your family.”

For Dessler, Morton Hall, the former home of the government department, was a “hall of distorted mirrors.” It was also one of the last places he stepped foot on campus before he was banned from communicating with all College personnel besides Chief Human Resources Officer John Poma. Dessler often expressed concerns about this ban in emails to Poma.

At the end of the fall 2015 semester, Dessler emailed Floyd to thank her for being a compassionate professor and taking care of his students. He also informed her that he had contacted the website Rate My Professors to dispute a comment that lowered Floyd’s overall score. At the time, this call boosted her score to a 4.0. He also offered her a gift, which she declined in her response.

“This was the most lovely email to receive, thank you sincerely,” Floyd wrote in the email. “Other than to know you needed someone to assist with your classes, I’m afraid I was not privy to the details. But I did stress the students many times how much you loved them, how your priority has always been to teach them, and how we would all get through the transition together.”

Floyd then forwarded Dessler’s messages to McGlennon and let him know that she had declined the gift. McGlennon also received email updates from Poma and William and Mary Police Department Chief Deb Cheesebro regarding the state of Dessler’s criminal cases. Once, he inquired if Dessler had access to mental health evaluation and care for his diagnosed medical condition while in jail. McGlennon also had email contact with Williamsburg and James City Council Deputy Commonwealth’s Attorney Cathy Black.

In February 2016, Dessler emailed government professor Michael Tierney, saying he believed Poma wanted to keep him from returning to campus, although his paid leave was initially scheduled to end March 1.

“Some heavy s–– is almost certainly coming the department’s way,” Dessler said in the email. “Cannot be avoided. No point in discussing yet, except to say that you should know this: John [McGlennon] is working to keep me from returning to the department. Stopping him, and restoring sanity to the department, may mean pulling on a string that goes back to Oct. 20. The unfairness to which I was subjected is a serious matter in the legal world. I know you do not believe I was treated unfairly. Right now, you don’t have to. But I would, if I were you, think hard about John’s silences regarding me.”

Tierney engaged in a multi-email conversation with Dessler, expressing interest in his career prospects and research projects and indicating that he would be interested in meeting Dessler to talk off-campus and catch up on life.

“I prefer [international relations] theory to legal drama,” Tierney said in an email. “Of course, if I am getting sued, I would love the heads up, but if this is just some administrative drama, I figure there are lawyers to deal with such nonsense.”

It is not clear how much each individual professor knew about Dessler’s medical and legal troubles, but Tierney told Dessler that there were a handful of professors who would be on his side.

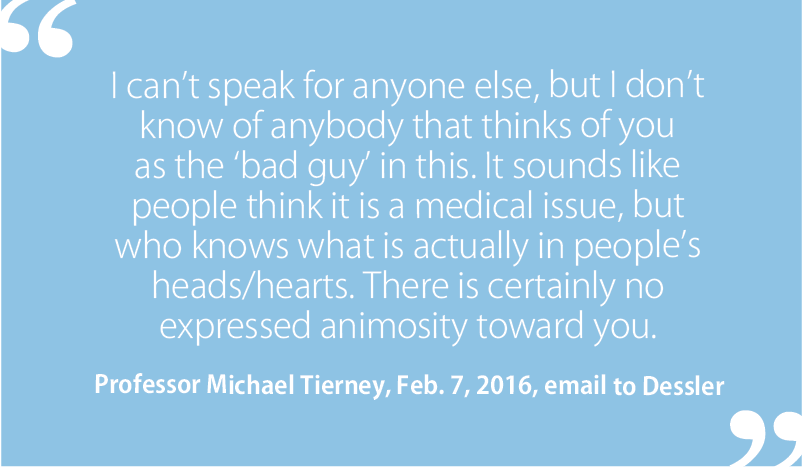

“I can’t speak for anyone else, but I don’t know of anybody that thinks of you as the ‘bad guy’ in this,” Tierney said in a Feb. 7, 2016, email. “It sounds like people think it is a medical issue, but who knows what is actually in people’s heads/hearts. There is certainly no expressed animosity toward you like there has been expressed toward other members of our department who have occasionally been on leave. … If you came back healthy, my assumption is that people would rapidly update their assumptions.”

It is unclear what McGlennon or each individual faculty member thought of Dessler based on the content of the FOIA emails and at what point the department realized he would not be returning. Multiple professors discussed the process of selecting office space in Tyler Hall, where the department would move in fall 2016, and made sure that someone was tasked with selecting an office for Dessler. While Dessler believes that he was effectively terminated as soon as he was placed on “inactive status,” it appears as if several professors planned on him returning to teach up until the day of his resignation.

It is not entirely clear what the future has in store for Dessler. A court date has not been scheduled for his lawsuit. He said he plans to move forward with Syntiro and has made a website for the initiative. Now, what matters most to him is that he lost his job and is working on changing the direction of his life.

“I lost my job and that was what was most important to me, so I’ve been kind of reorienting my life and I have not wanted to bother [anyone],” Dessler said. “I have kept the leadership of the Faculty Assembly apprised of my progress — for example, I sent them a copy of the lawsuit just so they’d know where things stand — but I am not in conversation with them. What I’m doing next is really thinking about a different life with a different set of friends, but I am sure I will be in contact with people at William and Mary again.”